Man in the Box

| "Man in the Box" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

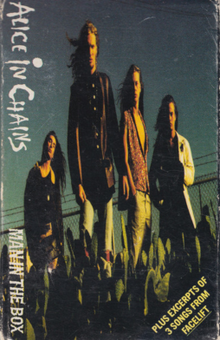

US commercial cassette single | ||||

| Single by Alice in Chains | ||||

| from the album Facelift | ||||

| B-side | "Sea of Sorrow/Bleed the Freak/Sunshine" | |||

| Released | January 1991[1] | |||

| Recorded | December 1989 – April 1990 | |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 4:46 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Composer(s) | Jerry Cantrell | |||

| Lyricist(s) | Layne Staley | |||

| Producer(s) | Dave Jerden | |||

| Alice in Chains singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Man in the Box" on YouTube | ||||

"Man in the Box" is a song by the American rock band Alice in Chains. It was released as a single in January 1991 after being featured on the group's debut studio album, Facelift (1990). It peaked at No. 18 on Billboard's Mainstream Rock chart and was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock Performance in 1992. The song was included on the compilation albums Nothing Safe: Best of the Box (1999), Music Bank (1999), Greatest Hits (2001), and The Essential Alice in Chains (2006). "Man in the Box" was the second most-played song of the decade on mainstream rock radio between 2010 and 2019.

Origin and recording

[edit]In the liner notes of 1999's Music Bank box set collection, guitarist Jerry Cantrell said of the song; "That whole beat and grind of that is when we started to find ourselves; it helped Alice become what it was."[2]

The song makes use of a talk box to create the guitar effect. The idea of using a talk box came from producer Dave Jerden, who was driving to the studio one day when Bon Jovi's "Livin' on a Prayer" started playing on the radio.[3]

The original Facelift track listing credited only vocalist Layne Staley and Jerry Cantrell with writing the song.[4] All post-Facelift compilations credited the entire band. It is unclear as to why the songwriter credits were changed.

Composition and music

[edit]"Man in the Box" is a grunge,[5][6] alternative metal,[7][8] hard rock,[6] and alternative rock song[9] that is widely recognized by its distinctive "wordless opening melody, where Layne Staley's peculiar, tensed-throat vocals are matched in unison with an effects-laden guitar" followed by "portentous lines like: 'Feed my eyes, can you sew them shut?', 'Jesus Christ, deny your maker' and 'He who tries, will be wasted' with Cantrell's drier, less-urgent voice," along with harmonies provided by both Staley and Cantrell in the lines 'Won't you come and save me'.[10]

Lyrics

[edit]In a 1992 interview with Rolling Stone, Layne Staley explained the origins of the song's lyrics:

I started writing about censorship. Around the same time, we went out for dinner with some Columbia Records people who were vegetarians. They told me how veal was made from calves raised in these small boxes, and that image stuck in my head. So I went home and wrote about government censorship and eating meat as seen through the eyes of a doomed calf.[11]

Jerry Cantrell said of the song:

But what it's basically about is, is how government and media control the public's perception of events in the world or whatever, and they build you into a box by feeding it to you in your home, ya know. And it's just about breaking out of that box and looking outside of that box that has been built for you.[12]

In a recorded interview with MuchMusic in 1991, Staley stated that the lyrics are loosely based on media censorship, and "I was really really stoned when I wrote it, so it meant something different then", he said laughing.[13]

Release and reception

[edit]"Man in the Box" was released as a single in 1991.[1] It is widely considered to be one of Alice in Chains' signature songs, reaching number 18 on the Billboard Album Rock Tracks chart at the time of its release. Loudwire and Kerrang both named "Man in the Box" as Alice in Chains' greatest song.[14][15]

The song was number 19 on VH1's "40 Greatest Metal Songs", and its solo was rated the 77th greatest guitar solo by Guitar World in 2008.[16] It was number 50 on VH1's "100 Greatest Songs of the 90s" in 2007.[17] The song was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock Performance in 1992.[18]

Steve Huey of AllMusic called the song "an often overlooked but important building block in grunge's ascent to dominance" and "a meeting of metal theatrics and introspective hopelessness."[10]

According to Nielsen Music's year-end report for 2019, "Man in the Box" was the second most-played song of the decade on mainstream rock radio with 142,000 spins.[19]

Music video

[edit]The MTV music video for the track was released in 1991 and was directed by Paul Rachman, who later directed the first version of the "Sea of Sorrow" music video for the band and the 2006 feature documentary American Hardcore. The music video was nominated for Best Heavy Metal/Hard Rock Video at the 1991 MTV Video Music Awards.[20] The video is available on the home video releases Live Facelift and Music Bank: The Videos. The video shows the band performing in what is supposedly a barn, where throughout the video, a mysterious man wearing a black hooded cloak is shown roaming around the barn. Then, after the unknown hooded figure is shown, he is shown again looking around inside a stable where many animals live where he suddenly discovers and shines his flashlight on a man (Layne Staley) that he finds sitting in the corner of the barnhouse. At the end of the video, the hooded man finally pulls his hood down off of his head, only to reveal that his eyelids were sewn together with stitches the whole time. This part of the video depicts on the line of the song, "Feed my eyes, now you've sewn them shut". The man with his eyes sewn shut was played by a friend of director Paul Rachman, Rezin,[21] who worked in a bar parking lot in Los Angeles called Small's.[22]

The music video was shot on 16mm film and transferred to tape using a FDL 60 telecine. At the time this was the only device that could sync sound to picture at film rates as low as 6FPS. This is how the surreal motion was obtained. The sepia look was done by Claudius Neal using a daVinci color corrector.[citation needed]

Layne Staley tattooed on his back the Jesus character depicted in the video with his eyes sewn shut.[23][24]

Live performances

[edit]At Alice in Chains' last concert with Staley on July 3, 1996, they closed with "Man in the Box". Live performances of "Man in the Box" can be found on the "Heaven Beside You" and "Get Born Again" singles and the live album Live. A performance of the song is also included on the home video release Live Facelift and is a staple of the band's live show due to the song's popularity.

Personnel

[edit]- Layne Staley – lead vocals

- Jerry Cantrell – guitar, talk box, backing vocals

- Mike Starr – bass

- Sean Kinney – drums

Chart positions

[edit]Weekly charts

[edit]- Facelift version

| Chart (1991) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Mainstream Rock (Billboard)[25] | 18 |

- Live version

| Chart (2000) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Mainstream Rock (Billboard)[25] | 39 |

Decade-end charts

[edit]| Chart (2010–2019) | Position |

|---|---|

| US Mainstream Rock (Nielsen Music)[19] | 2 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United States (RIAA)[26] | 3× Platinum | 3,000,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

Cover versions

[edit]Richard Cheese and Lounge Against the Machine covered "Man in the Box" in a lounge style on their 2005 album Aperitif for Destruction. Platinum-selling recording artist David Cook covered the song during his 2009 Declaration Tour. Angie Aparo recorded a cover version for his album Weapons of Mass Construction. Apologetix parodied the song as "Man on the Cross" on their 2013 album Hot Potato Soup. Metal artist Chris Senter released a parody titled "Cat in the Box" in March 2015, featuring a music video by animator Joey Siler.[27] Les Claypool's bluegrass project Duo de Twang covered the song on their debut album Four Foot Shack. In 2020, music group The Merkins posted a parody of the song on their YouTube channel,[28] featuring singer Joey Siler[29] as Pinhead from the Hellraiser film series.[30]

In popular culture

[edit]- Professional wrestler Tommy Dreamer used the song as his entrance music in Extreme Championship Wrestling from 1995 to 2001, and with his own wrestling promotion, House of Hardcore, since 2012.[31]

- The song appeared as a playable track in the video games Rock Band 2 and Guitar Hero Live.

- "Man in the Box" has been featured in films such as Lassie (1994),[32][33] The Perfect Storm (2000),[34] Funny People (2009)[35][36] and Always Be My Maybe (2019).[37]

- The song has been featured in TV shows including Beavis and Butt-Head (1993),[38][35] Dead at 21 (1994),[35] Cold Case (season 2, episode 13, "Time to Crime" in 2005),[35][39] and Supernatural (season 12, episode 6, "Celebrating the Life of Asa Fox" in 2016).[40][35]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Alice In Chains Timeline". SonyMusic.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 1999. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ Liner notes, Music Bank box set. 1999.

- ^ de Sola, David (August 4, 2015). Alice in Chains: The Untold Story. Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-1250048073. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Liner notes, Facelift. 1990.

- ^ "10 Grunge Albums You Need to Own". Revolver. September 16, 2014. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Lealos, Shawn S. (November 25, 2014). "The 10 best Alice in Chains songs". AXS. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (August 3, 2011). "The 10 Best Alternative Metal Singles of the 1990s". PopMatters. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham (March 12, 2012). "Metal Madness: Stage Dive Region". Loudwire. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Yglesias, Matthew (May 21, 2007). "The Ultimate Nineties Alt-Rock Playlist". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 24, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Huey, Steve. "Man in the Box". Allmusic. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Jeffrey Ressner (November 28, 1992). "Alice in Chains: Through the Looking Glass". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ "Jerry Cantrell Explaining Alice In Chains' "Man In The Box"". YouTube. April 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ "Layne Staley and Sean Kinney on dark songs and the meaning of "Man In The Box"". YouTube. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Childers, Chad (March 18, 2014). "10 Best Alice in Chains Songs". Loudwire. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ Law, Sam (March 30, 2021). "The 20 greatest Alice In Chains songs – ranked". Kerrang. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ "100 Greatest Guitar Solos". Guitar World. October 30, 2008. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "VH1's 100 Greatest Songs Of The '90s: Not Enough Pavement". Stereogum. December 12, 2007. Archived from the original on December 30, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "The Grammy Nominations". Los Angeles Times. January 9, 1992. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ a b Trapp, Philip (January 14, 2020). "Nirvana Were the Most-Played Band of the Decade on Rock Radio". Loudwire. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "1991 MTV Video Music awards". Rockonthenet.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2007. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ^ Rachman, Paul (March 27, 2014). "Me on the set of the Man In The Box video I directed '90 #tbt @AliceInChains". Twitter. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Rachman, Paul (May 12, 2018). "The man I cast in @AliceInChains' #ManInTheBox music video was nicknamed Resin and worked in a bar parking lot in Los Angeles called Small's". Twitter. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Baltin, Steve. "Q&A With Jerry Cantrell". Inked Magazine. Archived from the original on October 10, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Layne Staley's Tattoo Was Inspired By "Man In The Box" Lyric & Video". Feel Numb. December 8, 2010. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ a b "Alice in Chains Chart History (Mainstream Rock)". Billboard.

- ^ "American single certifications – Alice in Chains – Man in the Box". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Kitties In Chains "Cat In The Box" Is Childish, Immature And I Love It". 25 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-25.

- ^ "The Merkins". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2022-06-12. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ "Joey Siler". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2022-08-27. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ PINHEAD - "MAN IN THE BOX" (ALICE IN CHAINS PARODY), 23 August 2020, archived from the original on 2022-05-18, retrieved 2022-08-27

- ^ McNeill, Pat (April 17, 2002). The Tables All Were Broken, McNeill's Take on the End of Professional Wrestling As We Know It. iUniverse. p. 197. ISBN 978-0595224043. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Lassie (1994)". SoundtrackInfo. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Man In The Box em "Lassie" (1994)". YouTube. 3 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Man In The Box no filme "Mar Em Fúria" (2000)". YouTube. 17 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Alice in Chains - Soundtrack". IMDb. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Funny People Soundtrack". Whatsong. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ Allen, Ben (May 29, 2019). "Here's every song featured in Netflix romcom Always Be My Maybe". Radio Times. Archived from the original on 2019-10-16. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ "Beavis & Butt head Ice Ice Baby Vanilla Ice Man in the Box Alice in Chains". YouTube. 3 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Cold Case - S2 · E13 · Time to Crime". Tune Find. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Supernatural 12x6 : Alice In Chains - Man In The Box (Scene)". YouTube. 22 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved July 28, 2017.